Wading in to improve water quality at Pūkorokoro-Miranda

Addressing water quality can get very complicated when a catchment flows into an internationally significant 8,500-hectare coastal wetland, home to around 40 different migratory birds species and protected under the Ramsar Convention. The total catchment area is 6,000 hectares which includes about 9 dairy farms, and a mixture of other land use including sheep and beef farms and lifestyle blocks.

Welcome to Pūkorokoro-Miranda, located on the western coastline of the Firth of Thames/Tīkapa Moana.

Migratory birds gather here, including the red knots that fly all the way to Siberia and back every year, and the bar tailed godwits that migrate to and from Alaska. These migratory shorebirds need good food and safe resting places, and rely on the mudflats, shell banks and low-lying coastal land at Pūkorokoro-Miranda.

- 6,000ha total catchment area

- 26% of the catchment is dairy farms

- 8,500ha international Ramsar Wetland

- 40 different migratory birds

- 3 main types of farming (dairy, sheep, beef)

However, the Firth of Thames, once plentiful with marine life, is filling up with sediment. The main rivers (Piako and Waihou) entering the Firth originate inland in Waikato, flowing through land modified by land clearance, agriculture, and mining. The water that flows into the Firth deposits a gluggy layer of sediment and nutrients. Food sources for birds, such as worms, shellfish, and crabs can’t survive in this oxygen depleted habitat. Mangroves thrive in the mud and have expanded into the birds’ coastal habitat.

Living Water, a partnership between the Department of Conservation (DOC) and Fonterra, has trialled tools to improve freshwater in five catchments around New Zealand. Living Water chose the Pūkorokoro-Miranda catchment as a trial site because of the complex challenges and critical need to make substantial water quality improvements, said Sarah Yarrow, Living Water National Manager.

“There’s everything at stake in Pūkorokoro-Miranda”, said Yarrow. “High levels of sediment in the water, eroded from hill country and stream banks, flow down to degrade and reduce the internationally significant coastal shorebird habitat. Improving the water quality will deliver substantial improvements for the sensitive coastal environment and marine birds that rely on it. That’s why we chose to tackle these complex issues using a community-led ‘mountains to sea’ approach.”

Improving the water quality will deliver substantial improvements for the sensitive coastal environment and marine birds that rely on it. That’s why we chose to tackle these complex issues using a community-led ‘mountains to sea’ approach

Sarah Yarrow

Where do you begin in a complicated catchment?

The first step in any restoration project is to understand the issues to be resolved. That’s why Living Water conducted baseline ground research (called a Catchment Condition Survey) covering most of the properties in the 6000 hectare catchment, looking out for key water quality and ecological issues. This information helped prioritise interventions which can then be tested to measure their effectiveness. A major benefit of this survey is it’s relatively cost effective and easy to repeat for measuring change. Yarrow said an even greater benefit is that the survey engages landowners and collects their knowledge.

“Not only are surveys relatively inexpensive and easy to do, the Catchment Condition Survey allows direct engagement with landowners who can share their knowledge of issues and solutions tried over time in their area of the catchment”, said Yarrow. “Collectively the insights of many landowners add tremendous value to the recording of the physical and visible aspects of the catchment. The survey also helped increase landowners’ awareness of environmental issues, and gave them a view of their property in the context of a wider catchment. Understanding how run-off from your farm impacts landowners downstream is very important for getting communities to act together to improve water quality.”

The survey information was analysed and then loaded into the CAPTure tool. CAPTure is a GIS-based land information tool that holds land-use maps and soil maps. When the Catchment Condition Survey data is also incorporated the CAPTure tool creates a comprehensive snapshot of the catchment’s condition. It indicates where remediation efforts need to be targeted for the greatest impact.

Drawing on the CAPTure data, recommendations were made to landowners with high-risk areas most prone to run-off and erosion across the catchment, as part of the landowners’ Farm Environment Plans (FEP). These included planting poplars to combat erosion, creating detention bunds to manage sediment, and fencing/planting natives next to streams.

Living Water returned to Pūkorokoro-Miranda in 2023 to do a follow-up CCS and interviews with five landowners to assess the state of the catchment and gather insights. The survey covered 3,568 hectares (ha) of land, with 1,454 ha in the focus area of the Miranda Stream catchment. Efforts were made to align the survey with the 2017 baseline to provide meaningful comparisons and track change.

Some of the most visible gains were native planting now accounting for 34% of the total riparian vegetation, with 10.96kms of new native planting along waterways up 35% from the previous survey. Over 43kms of new fencing of waterways had resulted in a 45% increase in waterways where both sides exclude stock from entering.

‘These increases in native planting and stock exclusion fencing are significant gains’, said Yarrow. ‘They demonstrate an understanding and commitment by landowners to make changes that improve biodiversity and freshwater quality. Importantly they signal a change in attitude towards how we farm with nature rather than in competition with it. These social changes are every bit as important as the physical changes.’

While the FEPs were useful in getting environmental projects started on farms, many of the properties in the catchment are small blocks and don’t have FEPs. These blocks were important to consider, because they are often on steep areas around the catchment’s headwaters, that are a key source of sediment. If any sort of biodiversity and water improvements were to happen in the catchment, all landowners needed to be engaged.

The first step in any restoration project is to understand the issues to be resolved

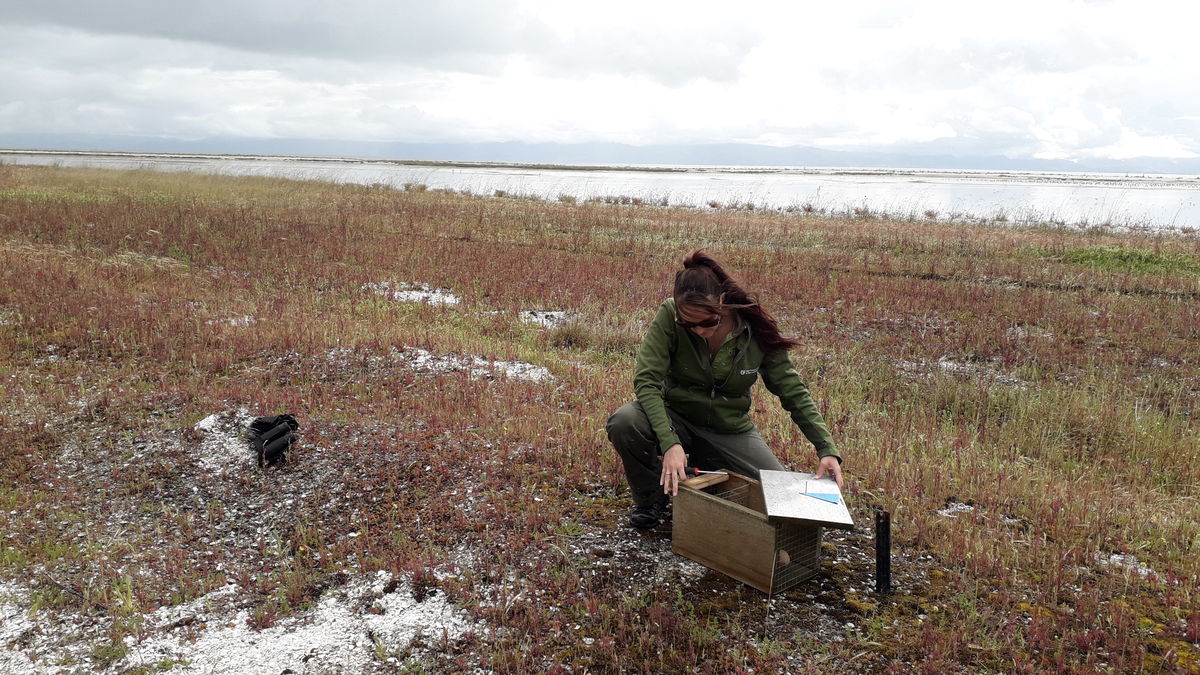

Living Water identified predator control projects as the way to engage with landowners.

“Every time we met with landowners, we’d hear about what damage possums were doing to their crops, fruit trees or vegetables,” said Dion Patterson, Living Water Site Lead and DOC Senior Biodiversity Ranger. “We wanted to provide the right tools and support to reduce predators in the catchment, which happened to align with the burgeoning Predator Free 2050 movement.”

In 2019 Living Water commissioned a survey to gauge landowner’s appetite for predator control - and whether they preferred to do it themselves or use a contractor. The findings showed there was already a broad understanding of the damage possums, rats and mustelids (stoats, ferrets and weasels) have on birds and crops, and overwhelming support for their control. The findings indicated predator control would be an effective way to engage with landowners who might not be as interested in other environmental improvement activities. It could build trust and credibility for activities such as fencing waterways and retiring steep land in the future.

A community workshop held in a woolshed in late 2019 was attended by about 100 landowners. It featured predator control experts (including trap suppliers, Waikato Regional Council, DOC, and a neighbouring catchment group). Presentations were given by other organisations such as the Western Firth Catchment Group (WFCG), Te Whangai Trust and Million Metres Streams, to increase understanding of environmental initiatives in the area and provide context.

“The workshop was a good way to meet a lot of the landowners, in particular lifestyle block owners we had never met. While talking to people about pest control, we could talk to them about what they were doing on their farms and where the opportunities existed to work with them in future,” said Patterson.

After the workshop, Trapinators and A12 possum traps were set up and operated in the catchment by landowners and an expert trapper contracted to the project. After 8 months operation a possum control monitor was undertaken. Despite anecdotes from landowners believing their ability to grow fruit and vegetables was proof of the success of the pest control, the monitoring suggested there were still moderate possum numbers present. A decision was made to ramp up efforts by deploying NZ Auto Traps AT220’s which to date appear to have increased kill rates on possums as well as killing rats. The expert trapper contracted to the predator control project has educated local landowners in pest control techniques so that after Living Water ended its involvement in 2023 the local community could continue the necessary work of predator control.

Dion Patterson

Collaboration the key to catchment management

Building on the success of the predator control project, Living Water and the WFCG decided to work together on a new project, called ‘Mountains to Sea’, which involved planting waterways and creating biodiversity corridors in the Miranda Stream Catchment. The WFCG is a group of residents and landowners whose properties extend 24 kilometres along the Western Firth from Waitakaruru to Wharekawa. These community members are focused on environmental restoration, primarily through pest control and planting. It has been running since 2018 and is chaired by local farmer Peter Roberts.

Joint activities in the Mountains to Sea project included Living Water-funded installation of detention bunds in the upper catchment to capture stormwater run-off, poplar pole planting to stabilise erosion prone hillsides, remediation of existing culverts to allow fish passage, and the planting of streams and drains. Living Water funded the plants while the landowners funded the fencing.

The success of the joint activities illustrates the importance of working with existing community groups, rather than competing with them for funding and membership. By funding an existing group with an active and committed membership, activities can be actioned immediately and progress achieved much faster than would occur with setting up a new organisation. By partnering with the WFCG, Living Water provided valuable funding for several years and empowered the WFCG to successfully seek alternative funding for future year’s activities when Living Water ended. This is an important legacy for Living Water’s work in the catchment.

In addition to planting and fencing streams, it became clear that more major interventions would be necessary to reverse years of damage to the fragile coastal ecosystem and significantly improve the wildlife habitat for migratory seabirds. Yarrow said when 60 hectares of coastal land became available to purchase Living Water recognised the opportunity and decided to act.

“Much of the land being offered for sale was low lying and marginal for farming but ideal for shorebird habitat”, said Yarrow. “A neighbouring landowner was interested in acquiring a portion of the land suitable for farming, which enabled Living Water to facilitate its joint purchase in 2018. DOC purchased part of the block (19.6ha) and designated it a Local Purpose reserve, Repo ki Pūkorokoro Reserve, that would increase habitat for shorebirds within the catchment. A very satisfactory outcome for all parties.”

Repo ki Pūkorokoro needed a management plan agreed to and supported by local community stakeholders. Living Water piloted a collaboration best practice model called ‘Incubate’, to establish a community trust that will ultimately control and manage the restoration of the reserve. The Incubate participants formed the Tiaki Repo Ki Pūkorokoro Trust (TRKPT) and includes Ngati Paoa, Pūkorokoro Miranda Naturalists Trust (PMNT), WFCG, Te Whangai Trust, Dalton Family Trust, Ecoquest, a community representative with DOC, Living Water, Waikato Regional Council and NZ Landcare Trust advisor to the TRKPT.

The Incubate process began with an independent facilitator carrying out one-on-one interviews to identify the participants’ social, environmental, and cultural aspirations. These findings were used to establish shared values, mission, and vision statements during a series of 3-hour meetings with the wider group. The meetings in Pūkorokoro-Miranda were held monthly for 18 months, leading to the TRKPT being established in 2019 and enabling ongoing development of the restoration plan. The restoration plan was completed in 2023, leading to the trust securing a DOC community grant to get things started. Living Water also introduced an MOU (Memorandum of Understanding) adapted from a collaborative project in Northland. Called an MEA (Mana-Enhancing Agreement) it is different to a regular MOU in that it seeks to build the mana of all signatory parties.

Changing land use, by creating a reserve, may not be a one-off approach in Pūkorokoro-Miranda or in other catchments where sea level rise and flood-prone environments are inundated more frequently.

It became clear that more major interventions would be necessary to reverse years of damage to the fragile coastal ecosystem and significantly improve the wildlife habitat for migratory seabirds. Yarrow says when 60 hectares of coastal land became available to purchase Living Water recognised the opportunity and decided to act

It is becoming increasingly clear that land use will need to change in the future. Living Water has completed a range of hydrological studies since 2013, to understand how to improve the environment for wading and shorebirds. Most recently in 2017-2020 hydrological modelling has informed the engineering design and consenting processes for the proposed regenerative wetland on the Pūkorokoro stream and stormwater drainage development.

To manage the impact of floodwater, early settlers dug drains through low-lying farmland in the catchment that flow into the sensitive coastal environment. Where these drains flow through the new reserve they will no longer be cleared out, to retain biodiversity. That could reduce the effectiveness of the stormwater management system. Consequently, landowners are currently working with an expert water engineering consultancy, Hauraki District Council, DOC, and PMNT, to create a channel that bypasses the reserve to minimise the impact on the regenerated wetland while delivering resilient floodwater management.

The Nature Conservancy has investigated Repo ki Pūkorokoro Reserve as a site for Blue Carbon. Blue Carbon is the carbon captured and held in marine ecosystems. The carbon sequestered by area in coastal wetlands - like mangroves, saltmarshes and seagrass meadows - is much higher than forested areas. Sequestration is the removal and storage of CO2, by restoring coastal wetland habitats their ability to remove carbon from the atmosphere and store it in soil layers is increased. The stored carbon could have a tradeable value on the voluntary carbon market. Depending on the outcome of the investigation, the project could provide alternative land use options for adjacent landowners wanting to retire land.

The global significance of Pūkorokoro-Miranda as an international feeding ground for migratory seabirds has been a driving factor in Living Water’s decision to work in the area

The global significance of Pūkorokoro-Miranda as an international feeding ground for migratory seabirds was a driving factor in Living Water’s decision to work in the area and the basis for many of the projects and trials to improve water quality. Living Water funded the Pūkorokoro-Miranda Naturalists Trust’s (PMNT) international travel to survey and monitor the migration of wading birds across the East Asian Australasian Flyway (Pūkorokoro-Miranda, North Eastern China, Korean Peninsula)

Over time the restoration work at Pūkorokoro-Miranda will improve wading bird habitat and food sources. However, the birds need access to shelter and food sources at the other end of their annual migration. Yarrow says PMNT’s involvement and successful relationship building has been a major contributor to DOC’s discussions with Chinese authorities on formal ecosystem protection initiatives.

“Migratory seabirds need protected habitats at each end of their journeys”, said Yarrow. “Our work at Pūkorokoro-Miranda has international and far-reaching consequences for the natural world. It’s a reminder to us of how inter-connected ecosystems really are, and how the decisions we make about land use here in Aotearoa New Zealand have impacts around the world. Therefore, we were very excited when an agreement between DOC and the Chinese Forestry Commission to protect areas of intertidal habitat in North Eastern China was signed at Pūkorokoro Miranda in 2015.”

While Living Water’s direct involvement in projects at Pūkorokoro-Miranda concluded in 2023, a decade’s worth of investment in community engagement ensures the gains made won’t be lost. Stakeholders have built relationships, participated in joint projects and experienced first-hand the benefits of working together to solve common problems. The Tiaki Repo Ki Pūkorokoro Trust, the Western Firth Catchment Group, and the Pūkorokoro-Miranda Naturalists Trust are just three of the significant community organisations committed to ensuring Pūkorokoro-Miranda is a world-class environment for New Zealanders and migratory sea birds to enjoy in the future

Read more about this and the other work in the catchment here and sign up to our newsletter to hear the latest updates

Ecological corridors at Pukorokoro-Miranda, New Zealand

Ecological corridors at Pukorokoro-Miranda, New Zealand