Waituna Lagoon, where complex wetlands coexist with food production

Waituna Lagoon is located 40 kilometres east of Invercargill and is part of the wider Awarua wetland complex (an area of 20,000 hectares) which is designated as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance. The wetlands provide habitats for a variety of native wildlife and migratory wading birds, and are an important area for mahinga kai species. The cultural significance to local iwi Ngāi Tahu was recognised under a Statutory Acknowledgement in the Ngāi Tahu claims Settlement Act 1998. The lagoon and wetland provide opportunities for recreation for the wider community including fishing, hunting and birdwatching.

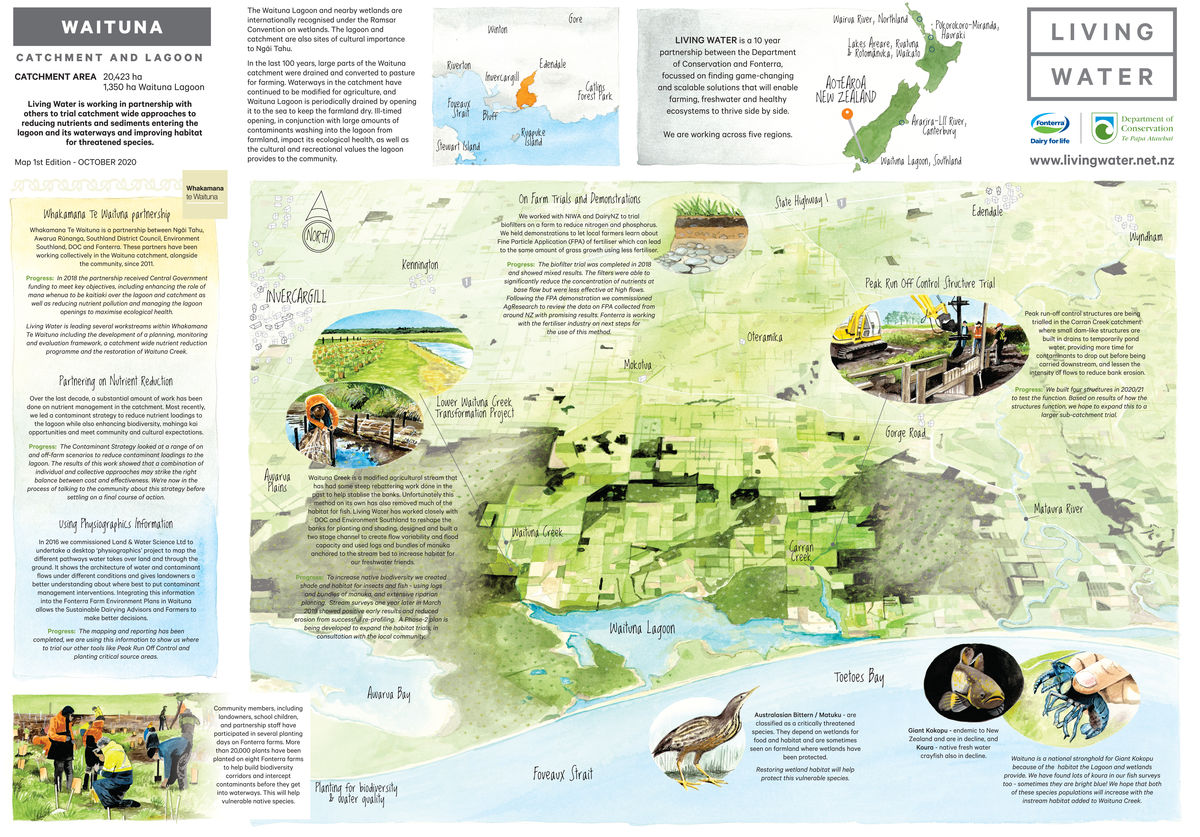

Waituna Lagoon is one of the best remaining examples of a coastal lagoon in New Zealand. It has relatively intact Ruppia beds (a type of aquatic plant) which have been identified as a key species in regulating Lagoon water quality and providing aquatic habitat. However, poor water quality is an issue for Waituna Lagoon. Waituna Lagoon sits at the bottom of an intensively farmed catchment. Over the last 150 years, about 70% of the catchment was converted from wetland and native bush to pasture for farming (mainly arable, forestry, sheep, beef and dairy). Waterways in the catchment have been channelised and deepened to ensure effective drainage. Waituna Lagoon is periodically opened to the sea to lower lake levels, which also allows for the movement of migratory fish. Productive land uses in the catchment and the modification of the waterways, wetlands and lagoon hydrology play a part in the poor water quality in the lagoon.

Sarah Yarrow

Cain Duncan

Pat Hoffmann

- 70% of the catchment converted from wetland and native bush to agricultural land over the past 150 years

- 80+ different species of bird in the wetland complex

- 130 properties in the catchment

- 5 main types of farming (arable, forestry, sheep, beef and dairy)

- 2000+ 'angler days' per year

A partnership approach

Living Water was active in the Waituna catchment from 2013 and was part of Whakamana Te Waituna (WTW), a wider partnership including Ngāi Tahu, Awarua Rūnanga, Southland District Council, and Environment Southland. The vision of Whakamana Te Waituna is “to improve the health and wellbeing of Waituna Lagoon, its catchment and community, for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations, while recognising and providing for the traditional relationship of Ngāi Tahu with their ancestral lake/rohe”. In 2018 the partnership received Central Government funding to enhance the role of mana whenua to exercise kaitiaki over the lagoon and catchment, to reduce nutrient pollution from the catchment and manage lagoon openings to maximise ecological health rather than simply land drainage.

Sarah Yarrow, Living Water National Manager, said several workstreams within Whakamana Te Waituna were led by Living Water including the restoration of lower Waituna Creek and a catchment-wide contaminant reduction programme.

“We were excited to work with other community partners in Whakamana Te Waituna, as we believe no single organisation has all the skills, knowledge and influence to improve freshwater”, said Yarrow. “We applied our knowledge and experience to a catchment-wide nutrient and sediment reduction programme, with the main goals of reducing nutrient and sediment loads to the lagoon and improving the quality of instream fish habitat within Waituna Creek”.

Waituna Lagoon is a highly valued coastal lake at risk of becoming eutrophic (dominated by algal slime) due to wetland drainage, vegetation clearance, land use intensification and the straightening of the lagoon’s main tributaries. This has led to increased sediment and nutrients moving through the water network and accumulating in the lagoon. In 2014, a technical advisory group recommended the volume of nutrients reaching the lagoon be reduced by 50 percent to ensure it’s long-term ecological health. Cain Duncan, Senior Environmental Partnerships Manager for Fonterra, said Living Water took that on board and considered how to get there.

“We started with a farm-by-farm approach, making sure all Fonterra farms in the catchment have Farm Environment Plans (FEP) and landowners are taking measures to reduce on-farm impacts on freshwater. Through Whakamana Te Waituna and Living Water we were able to provide extra funding for things like planting, fencing and wetland creation. Then we started looking at catchment interventions that could take us further towards our aspirations for the catchment”

Over Living Water’s ten-year partnership, there has been continued interest in on-farm sediment and nutrient reduction and a positive shift in mindsets towards freshwater and biodiversity improvements with landowners and partners involved in the catchment. “Working at a catchment scale naturally became the next step in the ongoing management of the area, giving the opportunity to share expertise, funds and have the greatest impacts on freshwater improvement” said Duncan. One of the first catchment “projects” by the trust was the purchase of a 584-hectare land buffer around the lagoon. The area is undergoing staged retirement and covenants to serve as protective zones around the perimeter of the lagoon.

403 hectares of the purchased land has been transformed into a mahinga kai pā. Changing land use in this way has assisted in the development of more community interaction opportunities and increasing community connections with mana whenua within the catchment and on the pā site.

We’re excited to be working with other community partners in Whakamana Te Waituna, as we believe no single organisation has all the skills, knowledge and influence to improve freshwater

Native Fish can thrive in farming environments

At the heart of the Waituna catchment is Waituna Creek. Once a gently meandering waterway, now after 150 years of modifications, in places it is little more than an agricultural drain, straightened and rebattered to stabilise the banks. Unfortunately, these actions have reduced its overall biodiversity health and removed much of the habitat for fish.

The Lower Waituna Creek transformation project is a multi-phase restoration project to increase the ecological resilience of Waituna Creek while meeting community aspirations to sustain productive agriculture with effective drainage and provide recreational and cultural opportunities.

Living Water chose two 200 metre reaches (500 metres apart) within a marginal strip of land along the Waituna Creek owned by DOC to trial the stream habitat rehabilitation actions. The transformation focused on improving habitat for fish by creating flow variability in the waterway with macrocarpa logs and bundles of manuka wired and anchored into the creek bed to provide shade and hiding places for fish.

An artificial flood plain was created by re-profiling the waterway banks into a two-stage channel. When in flood, the two-stage channel spreads the water, slows the flow-rate and allows sediment and nutrients to drop out rather than being flushed into the lagoon downstream. Extensive riparian planting created shade and habitat for insects that provide food for fish. This transformation was completed in March 2018. Stream surveys over the past three years show positive results and reduced erosion.

“The presence and abundance of native fish in a waterway is a good indicator the general health of the ecosystem”, said Pat Hoffman, DOC Senior Ranger and Living Water Site Lead for Waituna. “In our most recent fish survey the presence of juvenile lamprey was one of several exciting results. Lamprey have very high conservation values, being considered ‘nationally vulnerable’ to extinction, the same category given to the whio (blue duck). There was a significant increase in giant kōkopu and large longfin eels (tuna) which are native species considered at risk due to declining numbers. These results are proof of the success of the habitat improvement work in the creek.”

Although the in-stream logs had to be removed at the end of the project, due to the risk of them coming loose and causing flooding or erosion downstream, phase two of the restoration plan will be continued by the Trust. The aim is to build on the habitat creation concepts of phase one, exploring ideas for nutrient and sediment management and opportunities for recreation and enhancing cultural values while still maintaining effective land drainage. The project demonstrates the use of different restoration and water management concepts that could potentially be implemented throughout the catchment. It will be a highly collaborative project being co-designed by Iwi, councils, catchment engineers, drainage committee members and the wider community.

Advancements in reducing fertiliser application

In March 2017 Living Water commissioned a demonstration project on fine particle application (FPA) of fertiliser in the Waituna catchment. The project assessed the effects of applying nitrogenous fertiliser (urea) using the FPA method compared to conventional application of granular fertiliser. Duncan said studies suggested that FPA may achieve a similar pasture response to conventional application using less fertiliser and could result in greater fertiliser efficiency, reduced costs and potentially a reduction in nitrogen loss to water.

“The FPA system uses the same fertiliser as conventional methods, but applies it differently”, said Duncan. “The granules are ground up much smaller (approximately 1mm in diameter) which helps apply the fertiliser more evenly across pasture. The demonstration project allowed us to share the benefits of the FPA approach with local farmers at field days held in October 2017, February 2018 and July 2018. If more farmers use FPA of fertiliser there’ll be less nutrient run-off ending up in the catchment waterways, and the farmers will save money.”

Following the FPA demonstration AgResearch were commissioned to review the data on FPA collected from around New Zealand which showed promising results. Fonterra is now working with the fertiliser industry on the next steps for the use of this method.

FEPs and FPA of fertiliser won’t be enough to address all the sediment and nutrient issues in the catchment. A working party reviewed the existing science in the catchment and identified a suite of on-farm and off-farm options to reduce contaminants entering the lagoon. The resulting Contaminant Strategy looked at a range of tools to reduce contaminants entering the lagoon while enhancing biodiversity, mahinga kai opportunities and meeting community and cultural expectations. Yarrows said this work showed a combination of individual and collective approaches may strike the right balance between cost and effectiveness.

“Robust data allowed the Whakamana Te Waituna partners to discuss potential solutions with the community so that collectively, informed decisions could be made on where and what to do to achieve the biggest impact for the health of the lagoon”, said Yarrow.

Catchment-wide contaminant reduction strategies

Understanding the problem before trying to solve it is a key approach of Living Water. In 2016 Land & Water Science Ltd was commissioned to complete a desktop ‘Physiographic’ project to map how water travels over land and below ground in the Waituna catchment, under different rainfall conditions. The Physiographic approach is an integrated or ‘systems view’ that combines landscape attributes, such as soil type and topography, with the key processes affecting surface and shallow groundwater quality into a spatial format to identify, select, combine and classify the natural landscape factors that cause variations in water quality. It shows how water and contaminants flow under different conditions and gives landowners a better understanding of where best to put contaminant management interventions. Yarrow said the Physiographic information has been used by Whakamana Te Waituna.“The Physiographic approach provided the necessary information to enable us to prioritise nutrient and sediment mitigation tools across the catchment and invest the right solutions in the right place to improve water quality”, said Yarrow. “The Physiographic mapping allowed us to understand the problem before undertaking any interventions, either on-farm or at a catchment scale. The mapping shows where high losses of contaminants are likely to occur, then the right tool can be used in the right place along with better land management practices.”

As an example, the Physiographic information has shown where in the catchment to place the Peak Run-off Control Structures (PRCS) to target sediment and flooding run-off. Heavy rainfall that produces surface run-off is when most contaminants get washed into rivers and streams, damaging freshwater environments. Studies have shown that by reducing peak run-off, there are correlating reductions in suspended solids (61-94 percent), nitrogen (45-91 percent), and phosphorus (47-88 percent). There are also reductions in bank erosion and improvements to downstream aquatic habitat conditions.

Four PRCS were trialled in the Carrans Creek sub-catchment, that flows into the Waituna Lagoon. Small dam-like structures were built in drains to temporarily pond water, providing more time for sediment and contaminants to drop out before being carried downstream, and collectively lessen the intensity of flows to reduce bank erosion. Two of the PRCS were wooden weirs and two were constructed of rock.

“It seems the lack of demonstrated success of PRCS is the most likely barrier preventing their widespread adoption”, said Yarrow. “We wanted the trial to raise awareness of PRCS as a small, cost-effective tool to reduce contaminants and the eroding effect of run-off and gather evidence of how effective PRCS are at reducing peak flows and improving water quality.”

The PRCS in the trial were effective at dampening peak discharges and trapping sediment. The study estimated each structure retained 1-2 cubic metres of sediment over a period of 18 months.

To further reduce sediment, a large-scale off-line sediment trap was constructed with 90% of the flow of a major tributary in the catchment flowing through it, allowing sediment to drop out of the water before reaching the lagoon. The trap is regularly monitored to ensure it’s working as intended, to measure the volume of sediment caught in the trap and measure the size of sediment particles – fine sediment is more harmful to aquatic environments. If successful, there are plans for a second sediment trap in another major tributary.

Nature-based solutions have been a focus for Living Water. The upcoming trial of a 3-hectare wetland, that if successful could be scaled up to 16.5h-hectare wetland, is very exciting said Yarrow. “This trial aims to determine which plants species thrive in this type of environment, which species provide the best nutrient uptake, which plants are best from a cultural use perspective, how to get water to flow through the wetland and it will determine costs for future endeavours.”

The area for the constructed wetland is within a low gradient, deeply incised waterway which is typical to many lowland and intensively farmed areas around Aotearoa New Zealand, the lessons learnt could be applied to other regions. The wetland integrates within the mahinga kai pā and Te Rūnanga o Awarua’s vision of establishing water polishing ponds (wetlands) in and around the pā.

Alongside the construction of larger wetlands, reconnecting fragmented wetlands through riparian planting was identified as a way to enhance the ecology of the Waituna catchment. Living Water partnered with keen landowners and the Waituna Landcare community group to achieve large scale planting of riparian margins between fragmented wetlands and patches of native forest.

Community members, including landowners, school children, and partnership staff have participated in several planting days on Fonterra farms. More than 20,000 plants have been planted on eight Fonterra farms to help build biodiversity corridors and intercept contaminants before they get into waterways. Hoffman said the benefits of riparian planting are significant and far-reaching.

“Riparian plantings can act as biodiversity corridors and provide habitat connection for many wetland species, including birds”, said Hoffmann. “The plantings provide habitat for insects which drop into the stream and become an important food source for fish, especially giant kōkopu. The plantings stabilise the stream banks, reducing erosion and the need for mechanical drain clearing. And best of all by involving the wider community in planting days, the engagement creates buy-in and ownership of any ongoing maintenance needed beyond the project timeframe.”

Reconnecting fragmented wetlands through riparian planting was identified as a way to enhance the ecology of the Waituna catchment. Living Water partnered with keen landowners and the Waituna Landcare community group to achieve large scale planting of riparian margins between fragmented wetlands and patches of native forest.

Community members, including landowners, school children, and partnership staff have participated in several planting days on Fonterra farms. More than 20,000 plants have been planted on eight Fonterra farms to help build biodiversity corridors and intercept contaminants before they get into waterways. Yarrows says the benefits of riparian planting are significant and far-reaching.

“Riparian plantings can act as biodiversity corridors and provide habitat connection for many wetland species, including birds”, says Hoffmann. “The plantings provide habitat for insects which drop into the stream and become an important food source for fish, especially giant kōkopu. The plantings stabilise the stream banks, reducing erosion and the need for mechanical drain clearing. And best of all by involving the wider community in planting days, the engagement creates buy-in and ownership of any ongoing maintenance needed beyond the project timeframe.”

Living Water was set up as a 10-year national project to trial tools and approaches to improve water quality in five catchments, including Waituna Lagoon. Beyond 2023 when Living Water will end, Yarrow says it is inspiring to see that long-term partnerships have developed, and by working with farmers and local communities the health of the streams and waterways in Waituna will continue to improve.

“Living Water has been an advocate for changing the way freshwater catchments are managed” says Yarrow. “The future of farming will be different as we get better at farming with nature, and where the role of freshwater environments will be valued Waterways and wetlands are not only habitat for native birds, fish and insects and provide mahinga kai, they also drain away floodwater ensuring the surrounding agricultural land remains productive.

The future of farming will be different

Living Water was set up as a 10-year national project to trial tools and approaches to improve water quality in five catchments, including Waituna Lagoon. As Living Water ended in 2023, Yarrow said it was inspiring to see that long-term partnerships had developed, and with farmers and local communities working together the health of the streams and waterways in Waituna would continue to improve.

“Living Water has been an advocate for changing the way freshwater catchments are managed” said Yarrow. “The future of farming will be different as we get better at farming with nature, and where the role of freshwater environments will be valued. Waterways and wetlands are not only habitat for native birds, fish and insects and provide mahinga kai, they also drain away floodwater ensuring the surrounding agricultural land remains productive.”

Read more about this and the other work in the catchment here