Waituna Economic Evaluation

What is the problem?

The benefits that nature provides are not well accounted for within our economic systems, yet we rely on natural systems for our survival.

We benefit from the ‘free’ services that the environment provides to human society (providing raw materials, ecosystem services and assimilating pollution) but over time this has led to massive loss and degradation of nature.

If we are able to better account for the value of nature this could better support policy approaches and decisions for investment in restoring nature.

Living Water was interested to see if applying economic evaluation methods could help us to understand the costs and benefits of freshwater improvement actions within the Whakamana Te Waituna contaminant intervention project.

What has been done?

We carried out a cost benefit analysis (CBA) of the contaminant intervention work we have been doing with partners in the Waituna catchment, to quantify the net value of our interventions to improve the environment compared to if we didn’t do any interventions (e.g. Living Water didn’t exist).

Waituna provided a good case study as there is data on the health of Waituna lagoon through monitoring of native aquatic macrophytes that are a good indicator of lagoon health. We had also completed a previous piece of work on how and where to apply freshwater improvement interventions at a catchment scale, and this had been costed and assessed against taking action at farm scale only.

The evaluation focused on different scenarios that altered the risk of the lagoon shifting to an algal-dominated (poor health) regime. The analysis included two primary scenarios and a secondary scenario:

- 1) Catchment-level interventions scenario, such as purchasing and retiring farmland to create wetlands.

- 2) Farm-level interventions scenario, such as reducing autumn fertiliser application by 50%.

- 3) The 'no-land purchase scenario,' which was identical to the farm-level interventions scenario but without additional land purchase around Waituna Lagoon.

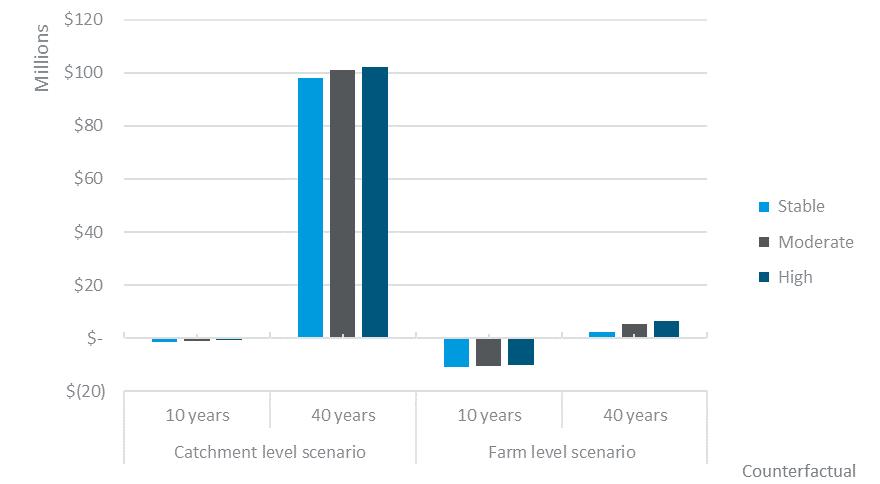

The cost-benefit analysis compared the costs and benefits of the three scenarios against three potential counterfactual situations: stable, moderate deterioration, and high deterioration of the lagoon.

What did the analysis show us?

Economic benefits outweigh costs over the long term

The evaluation showed that across a 10-year period, the quantified benefits of the project, such as the reduction in nutrient loads, were outweighed by the quantified costs in both scenarios (Net Present Value or NPV was negative). But this becomes positive under a range of sensitivity tests. When assessed at 40 years, the NPV becomes positive, with benefits significantly outweighing the costs. This is not surprising because most of the costs of the project are investment costs, whereas the benefits continue far into the future. This highlights the need for a long-term view when making investment decisions for environmental improvements.

Catchment level interventions are more beneficial than farm level interventions

The analysis identified the catchment-level interventions scenario as the most favorable scenario, with a higher NPV compared to the farm-level interventions scenario. Despite significant up-front costs, catchment-level interventions are likely to be more economically beneficial than farm-level interventions in the long-term with the largest benefits come from land purchase/land retirement. This supports planning for, and investing in, catchment level interventions (such as wetlands) to better achieve outcomes.

Cost Benefit Analysis doesn’t account for everything

The analysis did not capture some benefits that are outside the scope of the cost benefit analysis, such as cultural values and ecological significance. In a New Zealand context, these are factors that should be considered and given appropriate weight in decision making, as they offer considerable societal benefits that aren’t quantified within the CBA.

What has Living Water learnt from this project?

Economic analysis can be a useful tool to determine the benefits of restoration activities over time and guide investment decisions.

The Waituna cost benefit analysis highlights the importance of considering both short and long-term impacts, as well as potential benefits that are not currently monetised.

The analysis also emphasizes the importance of innovative mechanisms for monetising ecosystem services in order to incentivise land stewards to provide for natural habitats on their land, such as biodiversity credits and public procurement funds for environmental outcomes.

Decision-makers need to consider the benefits that sit outside the cost benefit analysis and assess the long-term impacts to make an informed decision.

Living Water has recognised that for nature-based solutions, like wetlands, to be financed and implemented across catchments, there needs to be evidence that their investment and longer-term value outweigh alternative shorter-term solutions across individual farms.

Who could use this information?

Any agri-business, catchment groups, farming communities, local and central government, NGO’s, banks and funding agencies.