How we can re-imagine productive landscapes to include wetlands

Today is World Wetlands Day, a day founded by the Ramsar convention on wetlands to raise awareness about the plight of wetlands and to reverse their rapid decline worldwide. The 2023 theme is wetland restoration, which has been a key focus for the Living Water partnership with all five sites having important wetlands, two of which have Ramsar status. The five catchments are in significant dairying regions that each face their own unique challenges (read about the catchment selection process here, and background on each of the issues being addressed in each catchment here).

Wetlands and people

The rise and fall of our waterways and tides is as sure as the sun rising each morning. Since the arrival of European settlers’ in Aotearoa New Zealand in the 1800s, our water networks have changed both naturally and with significant human modification, meaning we are now living and farming in areas that were once wetlands, mudflats, floodplains or riverbeds.

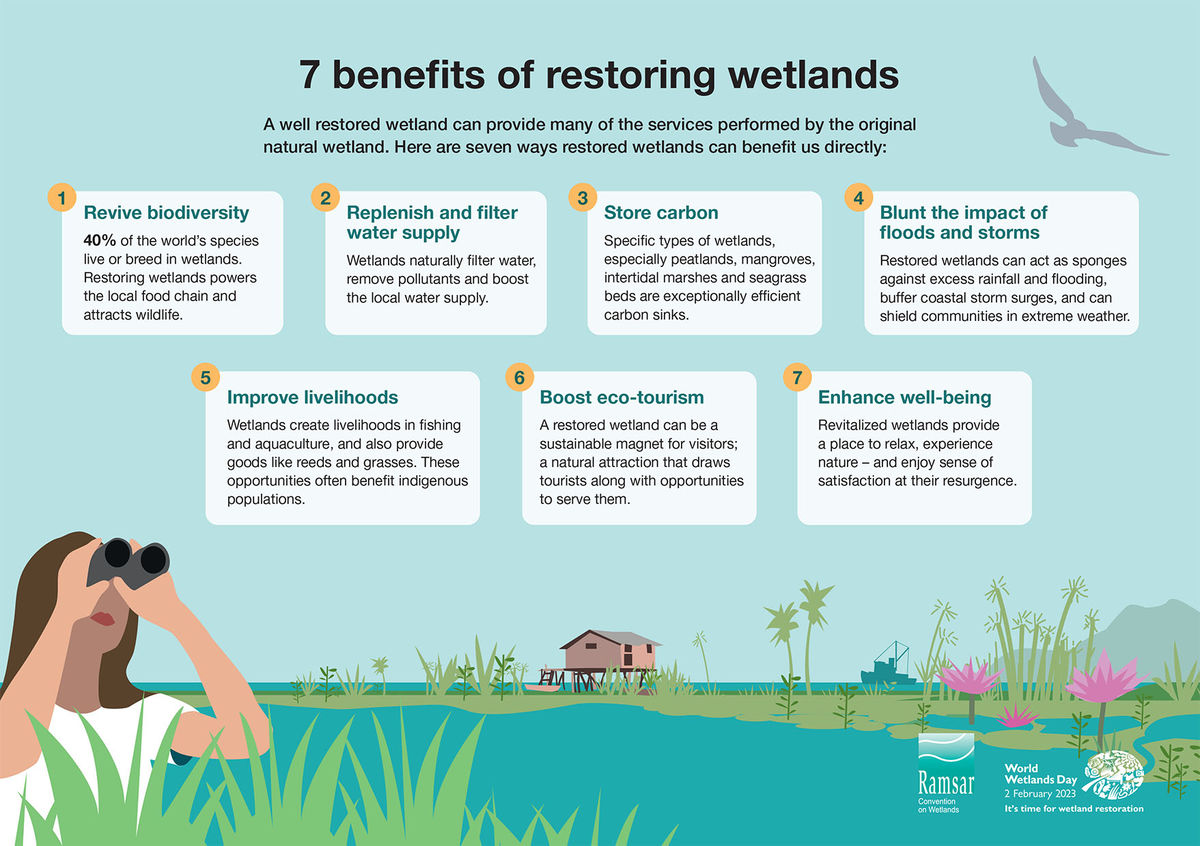

Wetlands have been likened to the kidneys of the earth because they filter out nutrients and contaminants that move through the catchment before they get to rivers, lakes and estuaries. As water moves through a wetland, sediment settles out and wetland plants use the nutrients for growth. This combination prevents the excessive growth of nuisance aquatic plants and algae that can upset the ecological balance of our lowland waterways and make them unsafe for recreational use.

People have become disconnected from the landscape and water around us, not associating that our way of life has contributed to issues like flooding and drought by using engineering to control water flow. When it rains, we want water drained away from the land as quickly as possible to prevent flooding. In both urban and rural areas, we have done a phenomenal job of building seawalls, tile drains, drainage networks, stormwater systems, locks, bridges and other water management interventions.

In agricultural catchments, environmental issues landowners are facing include flooding, droughts, land erosion and soil degradation. All these challenges are being accelerated by climate change. For biodiversity, there has been extensive wetland and stream habitat loss, especially in lowland areas where there were once large wetlands. Over time, water quality has been degraded and legacy nutrient and sediment issues remain.

The Living Water partnership has looked at interventions to improve these issues. Some small-scale trials like in-stream sediment traps, two-stage channels and in-stream habitat additions have been successful. These on-farm interventions alongside good farm management practices and changes to environmental limits will make improvements to freshwater. Farm-scale interventions are already being incorporated in Fonterra’s Farm Environment Plans as they can generally be used in existing waterways and farming systems. A key lesson from Living Water’s 70 trials is that these farm-scale interventions won’t have a significant enough impact on their own.

A theme that constantly reoccurs through our work is how nature-based solutions, especially wetlands provide more benefits than engineered interventions. Wetlands can reduce nutrient losses, prevent flooding, store water, act as carbon sinks, and provide habitat for our amazing fish, birds, plants and invertebrates.

If we learn to work with the ebbs and flows of water then we can continue to live and farm, just in a different way.

Working with nature: enabling wetlands to do their thing

Wetlands protect farms (and urban areas) from flood damage, while also storing water for times of drought. For wetlands to work effectively, we need to understand how the water moves through a catchment, as this differs across all catchments and during different rainfall scenarios.

The flow of water through a catchment depends on the landscape characteristics. Some areas will absorb water more easily than others depending on soil and rock types, slope gradient, etc. This can vary greatly across a catchment, even from paddock to paddock. Water travels over the surface of the land and through the networks of pores and caves below the land. We also need to understand how long it takes water to move from land to waterways so we can target actions. For example, does it flow downstream quickly, or does it sit on the surrounding floodplains and release slowly? This variation is what naturally determines where water gathers in the landscape and forms wetlands.

This data has previously been difficult to obtain. Living Water has been working with Land and Water Science to make landscape data more accessible to landowners by supporting the development of an online platform for their spatial mapping tool called LandscapeDNA. This information can tell us where wetlands once were, where water flows and why it takes a certain path, where ephemeral waterways are and help us identify areas that are critical sources of contaminants. In the Waituna catchment in Southland we’ve been using the data to determine where strategically placed large-scale wetlands would have the best outcomes for protecting Waituna Lagoon. An update on this project will be available in March 2023. In the meantime, the data has been used to place several peak run-off control structures into the water network. These are designed to slow the flow of water entering the creek and lagoon, reducing sediment and nutrient losses to these sensitive waterways.

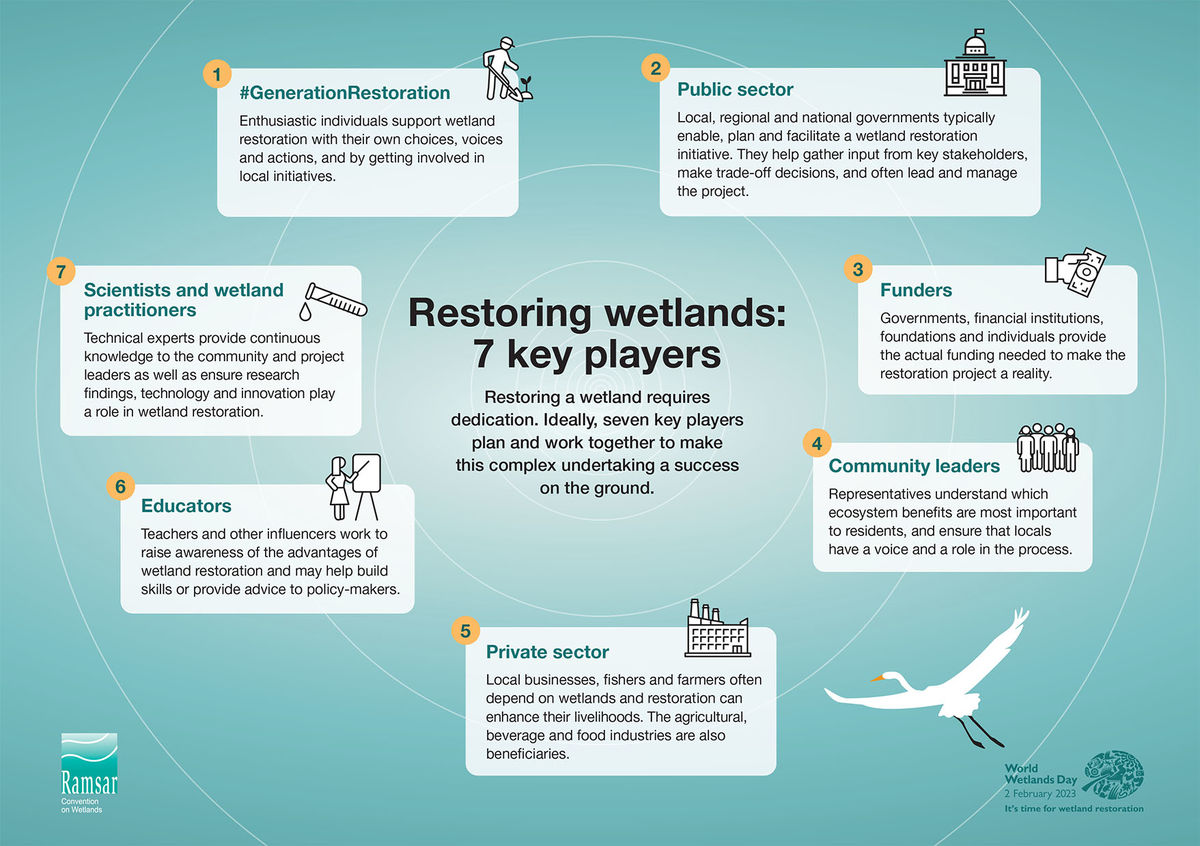

While accurate spatial data is necessary, the combination of science supported by landowner knowledge and Mātauranga Māori will produce the best solutions for freshwater and ecological health. Although te ao Māori perspectives on the environment differ between iwi, hapū and whānau, they usually emphasise the concept of mauri (life force) that connects humans with the environment – if the environment is in good health, the people are in good health.

Working with iwi on Living Water projects has allowed us to learn about the landscape through stories passed down over generations, like where large natural wetlands once were and what species were once abundant there. Alongside this, landowners’ in-depth knowledge of their farms and local areas provides key information about what happens to water on their land, what areas are susceptible to flooding and the layout of rural drains that now criss-cross farmland in place of the once large wetlands.

The enduring lesson we’ve learnt from working with others is that while partnering can be difficult and reasons for wanting change will differ, the way forward is to focus on shared outcomes for freshwater and the community.

We’ve put together information on partnership planning here and establishing a partnership here. You can also read about a unique Mana Enhancing Agreement approach used in the Waimā Waitai Waiora partnership in Wairua, Northland here.

The Living Water whakataukī is: “He waka hourua, he waka eke noa”. This translates to ‘a waka with two hulls bound by a common kaupapa or purpose’. It acknowledges though indigenous and non-indigenous peoples may be willing to get into the same waka and collaborate on a vision, objectives and outcomes, they can also maintain ‘separate hulls’ to preserve and advance the knowledge, institutions and practices of their own cultures

How do we do it?

Many of our Living Water projects encompass the protection and restoration of wetlands in different ways:

Farming with Native Biodiversity is a national pilot project to help farmers and on-farm advisors grow their understanding of biodiversity (like wetlands) and build restoration and protection actions into Farm Environment Plans. Ultimately, we hope that wetland protection and restoration will just become another key part of a resilient farming system.

In the Wairua catchment, Northland there are two large remaining wetlands, Otakairangi and Wairua. There are also dozens of small, isolated and fragmented wetland and riparian forest remnants, including fen, bog and marsh that are surrounded by farmland. To complement our work supporting farmers to make on-farm changes, we’ve been working closely with mana whenua through the Waimā Waitai Waiora partnership to develop farm environment and water quality improvement plans for 230 farms, incorporating sustainable land management practices and the principles of mātauranga Māori. The overall project goal is to reduce sediment transport into the Kaipara Harbour. Together we’ve planted over 100,000 trees in the catchment. The relationships built through this partnership ensures freshwater improvement work will continue after the Living Water trials finish. Ngā Kaitiaki O Ngā Wai Māori have taken over the monthly water quality monitoring in the catchment and are working directly with landowners to understand water quality through the catchment and what species are living in the wetlands and surrounding waterways through eDNA sampling, netting and electric fish.

The Pūkorokoro-Miranda, Hauraki catchment – located on the Firth of Thames/Tīkapa Moana, flows into an 8,500-hectare Ramsar-protected coastal wetland. The key focus is restoring and reconnecting the coastal wetlands and freshwater ecosystems with a community-led ’mountains to sea’ approach. The Coastal Wildlife Habitat Acquisition and Restoration Project involved the purchase of 19.6ha of farmland so it could be retired and become a designated Wildlife Management Reserve made up of freshwater and estuarine wetlands. The restoration of this land will improve breeding, roosting and feeding conditions for the migratory shorebirds that utilise this unique coastal area on their round-trip journey from New Zealand to Alaska for breeding each year.

The coastal wetlands of Pūkorokoro-Miranda could also become a site for generating blue carbon credits. Coastal wetland systems protect against sea-level rise and storm surges, and the mangroves, marshes and seagrass protect against coastal erosion. If the site is deemed to be sequestering enough carbon it may become an area where investors can help pay for restoration. You can read more about this here.

The Waikato Peat Lakes are a rare ecosystem, classified as acutely threatened. The focus is restoring the peat ecosystems which is very difficult because peatlands form over tens of thousands of years. At Lake Ruatuna we’ve worked with the community restore the wetland lake margins, including removing plant pests like willow and nuisance weeds like ludwigia, replacing it with native trees to provide shade. Sediment traps were constructed around the lake and have recently been planted with kuta to help slow the flow of water, allowing nutrients and sediment to drop out before they enter the lake. The locals of Ōhaupō have adopted the peat lakes, putting up signs welcoming people to the peat lakes and bringing attention to the birds that depend on the wetlands. Perhaps the most significant community buy-in for the future of the lakes is local iwi Ngāti Apakura establishing Pā harakeke/Rongoā (traditional Māori medicine) garden and Nature Education Trail. Eleven different varieties of harakeke have been planted around Lake Ruatuna, providing habitat for wetland birds and invertebrates as well as materials for weaving and traditional medicine. The Manga-o-tama Catchment Project expands on Living Water’s existing work in the catchment, bringing together iwi, regional and district council, landowners, and conservationists to work on a catchment-wide approach to improve water quality and restore habitat for native biodiversity along the Manga-o-tama Stream. In October 2021 the Waikato River Authority (WRA) approved $388,000 of funding for a two-year work programme.

The Ararira-LII, Canterbury catchment is a significant spring-fed tributary of Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere, New Zealand’s fifth-largest lake and an important wetland ecosystem. Our focus is transforming the rural waterway network as it is the last remaining habitat for freshwater fish, plants and invertebrates on the Plains and it carries a significant amount of water (and contaminants) to Te Waihora. The Re-imagining a Lowland Drainage Network Project builds on a number of smaller-scale trials undertaken in the catchment, a key one being transforming the rural drains back to a more natural state by restoring wetland marginal strips and by protecting and restoring the remaining Yarrs Flat wetland. An ‘Implementation Guide’ produced by the project team will be able to be used by councils and communities across New Zealand to do something similar – it’s on track to be completed in April 2023.

Waituna Lagoon, Southland and its surrounding wetlands are a Ramsar-designated site, teeming with native biodiversity. Living Water commissioned Land and Water Science to undertake a desktop Physiographics Project, mapping the flow of water through the catchment this project was the catalyst for the development of LandscapeDNA. The physiographics data has informed the majority of mahi underway in the catchment to help minimise land-use impacts on the lagoon. This includes the Waituna Catchment Nutrient Reduction Project, aimed at improving on-farm practices and ensuring the right contaminant management tools are used in the right places. Several organisations and local rūnanga have joined forces under the Whakamana Te Waituna Partnership to work together on better catchment planning and integration.

The Waituna Creek Restoration Project included two 200m stretches of the creek being used as trial sites for adding back wetland and fish habitat. Research from seven years of monitoring show the improvements have paid off with an increase in native species such as the giant kōkopu, large longfin eels/tuna and piharau/kanakana/lamprey. During the 2021/22 summer drought, the added habitat provided refuge for giant kōkopu when water levels got very low.

A Planting Biodiversity Corridors Project helped reconnect fragments of wetland scattered across the Waituna catchment by engaging local communities and landowners to plant margins along the banks of rivers and streams between existing remnants.

Enduring lessons: Wetlands are a key nature-based solution for Aotearoa New Zealand

Early settlers did a remarkable job of draining New Zealand’s swampy, peaty wetlands without the help of machinery. It’s hard to imagine the back-breaking work of clearing scrub and digging long straight channels to drain water from the land. These modifications resulted in the rich farmland that became the backbone of New Zealand’s economy and later the sprawling urban areas many now call home.

As a society we now have more appreciation and understanding of how vital wetlands are for humans to exist on earth. They are a nature-based solution, that when integrated into farm and catchment planning provide beneficial outcomes for water, climate, soils, biodiversity and farm resilience. Instead of seeing them as wasted, unproductive areas, we are slowly moving towards protection and restoration of these complex ecosystems.

To preserve the mauri of freshwater the future of farming will be different. We need to reimagine waterways in productive landscapes, from rivers down to rural creeks and this requires a co-design approach. We need to take the time to understand each other and work together because no single organisation or sector has all the skills, knowledge and influence to improve freshwater. By partnering together and using our unique strengths, we can accelerate freshwater improvement for Aotearoa New Zealand.

Links to other wetland information

DOC information on wetlands and why they are important

Magical places – 40 wetlands to visit

Managing wetlands as farm assets

The Wetland Handbook Series published by Manaaki Whenua